Irrespective of moments of controversy, like when

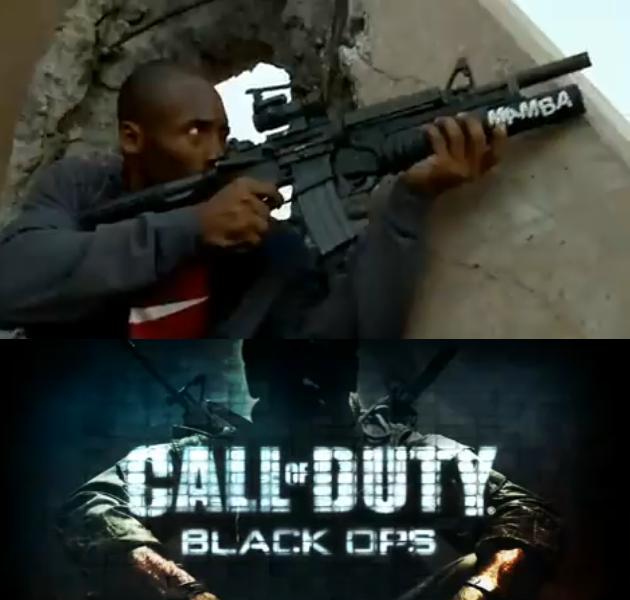

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UmZ3qzt8mM”>Kobe Bryant appeared as a sniper in a Call of Duty television advertisement, the holiday season is the time of year when video games are most in public view. This year is no different, as the onslaught of games released between now and the New Year constitutes a veritable gamers’ paradise of mostly sequelized titles that run the gambit of genre and style. As most of us are probably aware, since mainstream journalism has been sounding the alarm for several years now, top selling video games are more profitable than high grossing films. There are a lot of reasons for this, not the least of which is the fact that across generation, race, and class, games have become a—if not the—dominant form of entertainment in American households. Last year’s top-selling game, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 eventually exceeded $1 billion in sales. Call of Duty 3, just released in November 2011, grossed over $400 million on the first day, making it the all-time best-selling property of any form on a single day.

In addition to exposing these bottom line figures for the industry as far-outpacing sales in music, films, and television, popular news sources have also informed us that gamers are not who we thought they were. The impression of the average gamer as a socially awkward fourteen-year-old sequestered in his parents’ basement has been recanted and deconstructed enough in reports from news outlets as disparate as Fox News, The New York Times, and NPR. Recently, Michael Abbott has identified a convincing set of popular tropes used in mainstream media to talk about games. Suffice to say, it is now trendy and obligatory to document the cultural saliency of video games. These leading accounts about the “grown up” and changing status of gaming culture has led to a public reassessment of gaming demographics—of who we imagine plays games—in ways that create, I argue, some problematic assumptions about authorship, agency, and consumption.

To this end, there is now greater public awareness around the fact that the average gamer is thirty-five, and aging. It is also much touted that at least forty percent of gamers are women, and it is probably not surprising that nearly seventy percent of American households have a console or PC that is used for gaming.1 What may be less apparent in the current public consensus about the existence of a more diverse mass population of gamers is, as Adrienne Shaw has pointed out, that “new definitions of game culture are never used to question the constructed past of video game culture’s insularity, maleness, and youthfulness.”2 That is, not only does the current public discourse around games treat any deviations from the gamer stereotype as new and changed, such accounts are often ever skeptical of both the “original” (constructed) image of gamer as white geek and the “new” (improved-less-reclusive-hipper-more-diverse gamer) in ways that are ultimately re-pathologizing.

Regarding race, two trends have emerged as a part of the corrective shift toward an emphasis on gaming demography in popular discourse. The first of these trends draws attention to the fact that the vast majority of mainstream narrative games fail to include characters who reflect the now common sense notion of a more diverse gaming consumer base. The most popular video games continue to reinforce a de facto white maleness within game worlds. In fact, part of the (sometimes) subtle, but nonetheless consistent, media backlash against game culture is the popular conviction that video games are violent, racist, and sexist. Statistical analyses like the widely-cited report conducted by Children Now are used to confirm the rampant circulation of stereotypes (such as “African American females were far more likely than any other group to be victims of violence” )3 and to criticize the under-representation of minorities in games (as such the “Virtual Census’” findings that “white characters account for 84.95 percent of all primary characters,” while outside of sports games, black people are mostly “featured as gangsters and street people”).4 I am not suggesting that these comprehensive analyses have not been both necessary and instrumental in illuminating some of the disappointing realities and need for systemic change in the video game industry. I am suggesting, however, that mainstream journalism often uses statistics like these to codify the conversation about games and race around issues of representation.

The popular iteration of this trend,as evinced in the Resident Evil 5 debates, argues that with representations of blackness in particular, we may rightly conclude that there are coons, bucks, winos, crack heads, minstrels, and gangstas galore. Another case in point: the recent discussion of Letitia, a black woman wino/dumpster-diver (is she homeless?) who appears in the critically well-received sci-fi futuristic thriller, Deus Ex: Human Revolution.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Gamers, pundits, and bloggers have been swift and deliberate in demarcating Letitia, who has been called a character who “swims in the same dirty stream of ideas that gave America the welfare queen myth,”5 as emblematic of the ways in which image, voice-acting, and plot details combine to perpetuate stereotypes within video games—despite the much-acknowledged diversity of actual gamers. The responses to this image and to others like it demonstrate that popular audiences are primed to identify types and debate the extent to which such imagery is reductive, regressive, parody, or satire. Put another way, gamers, fans, and journalists are on the case when it comes to stereotypes and representational biases.

The other trend in this regard espouses a concern that even though video games, on the whole, reflect little cultural diversity that ventures beyond stereotype, —paradoxically—Black and Hispanic gamers are said to spend more money on games and play for more hours than other groups. What conclusions are we to draw from the finding that “Latinos, who play more per day than whites and form 12.5 percent of the population, are only 2 percent of characters”?6 Or, of the fact that low-income families play more games than high-income families? If it is commonly remarked that violence, racism, and sexism sell in games, and people of color, along with the economically disadvantaged, are playing games the most, is this ironic? Tragic? A cultural embarrassment?

Even though the intention behind a focus on gaming statistics may be to expose parity issues within the industry, there are ways in which amplification of the numbers narrows the conversation in unintended ways. For instance, is all too easy to be left with a compounding sense of passive, uncritical, and exploited minority gamers who spend a lot of time consuming the denigrated content of an already suspect medium. Further, the ways in which the shifting public perception of gaming relates to meta-discourses on race has consequences for how we as media scholars assess avenues for scholarly contribution.

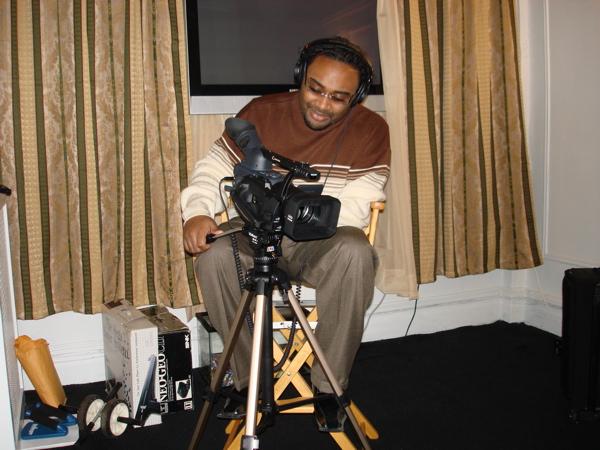

A focus on demography and representation tempts us to miss the ways in which “new,” non-white, gamers participate in gaming culture in highly active, resistant, and, importantly, productive ways. What is most interesting to me in this moment is the overlooked fact that Black and Hispanic gamers are creating media every day to criticize problematic practices, speak directly to developers, and to start their own new media production companies. Here I am thinking of a growing, vibrant list of personalities, authors, machinima directors, and actors in the gaming community, including: the writers at Minority Gamer, Cori Roberts of Gameinatrix, Blackessence, the many hosts of Raw Game Play, Michael Hurdle, The Latino Gamer, and many more. For example, Blackessence produces video tutorials about machinima, a style of filmmaking that uses game play footage. She also maintains a YouTube channel intended for women gamers, and she talks extensively about what it means to be a black “Lady Gamer.” Her videos have become so popular that she was invited to visit Electronic Arts (the developer that distributes The Sims). She explains, describing her visit: “And for some reason the company knew who I was, well that Sims department. They knew who I was because they saw the video, the video had been passed around, and everybody recognized me everywhere I went.”7

Click here to view the embedded video.

The verb that I use in my analyses of new media productions like the ones created by Blackessence is “grinding.” Grinding most often refers to the way players “level up” and improve their characters in time-consuming role-playing games. The term emphasizes the monotony inherent in the leveling process but it is also often used with pride. As I survey the ways minority gamers actively contribute to gaming culture, the term has also come to signify the laborious persistence and measure of creative violence that minority cultural agents exercise within a culture that frames them primarily as consumers and outsiders. As Michael Hurdle, founder of Raw Game Play, says at the end of one of his many assessments of the industry, “We’re grinding like everybody else.”8 In a “state of the union” address on the topic of racism, entrepreneurship, and gaming, Hurdle further insists: “No matter what, no matter how much racism is out there, we’re going to strive, we’re going to trump…. I just want to let you guys know, we are here to stay, we aren’t going anywhere.”9

These new media authors and their productions are a substantial part of gaming culture; they offer complex demonstrations of how players negotiate gaming and spectatorial practices. The works challenge us to broaden our notions of gaming culture by decentralizing the game and its images as objects of study and by amending who we identify as agents in our conversations about race and video games.

Image Credits:

1. Kobe Bryant and Call of Duty Advertisement

2. ESA’s Gaming Demographics

3. Michael C. Hurdle

Please feel free to comment.

NOTES- Reports by Nielsen, The Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Entertainment Software Association have been particularly influential in this regard.

- Adrienne Shaw, “What Is Video Game Culture? Cultural Studies and Game Studies,” Games and Culture 5, no. 4 (October 1, 2010): 408 (emphasis mine).

- Children Now, Fair Play?: Violence, Gender and Race in Video Games, December 1, 2001, 23.

- Dmitri Williams et al., “The Virtual Census: Representations of Gender, Race and Age in Video Games,” New Media & Society 11, no. 5 (2009): 825, 830.

- Evan Narcisse, “The Worst Thing About ‘Deus Ex: Human Revolution’,” Time, August 31, 2011, http://techland.time.com/2011/08/31/the-worst-thing-about-deus-ex-human-revolution/.

- Dmitri Williams et al., “The Virtual Census,” 831.

- EssenceOfTruth. “Get It Right, People: The Difference Between Girl Gamers, Female Gamers, and Lady Gamers…” YouTube, October 19, 2010.

- RawGamePlay, “DO NOT CLICK UNLESS YOUR READY TO HEAR THE TRUTH,” YouTube, August 31, 2010.

- RawGamePlay, “Racism In The Video Game Community Full Version (Watch If You Dare),” Youtube, September 7, 2010.